Welcome back to the Short Fiction Spotlight, a weekly column dedicated to doing exactly what it says in the header: shining a light on the some of the best and most relevant fiction of the aforementioned form.

Seems like Spectral Press has been in the news a whole lot lately; at least, the news I read—and write. A few Focuses ago we heard about The Spectral Book of Horror Stories, an exciting new anthology inspired by the cult classic Pan and Fontana annuals of the 60s and 70s. Simon Marshall-Jones’ indie outfit was also acknowledged by the British Fantasy Society with a number of award nominations, most notably for Best Small Press—this for the third time in a row, I think—but also for several stories by Steven Volk.

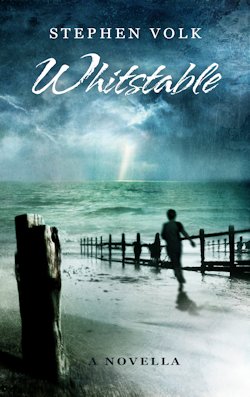

You might not know the name—he hasn’t written a whole lot of prose fiction—but Brits in particular will be familiar with his notorious Halloween hoax show, Ghostwatch, as well as the tremendous ITV series Afterlife. Afterlife’s cancellation was a Bad Thing, believe you me, but it did come with something of a silver lining: in the aftermath, Volk took to the short fiction form like a fella possessed. To wit, this week, we’re going to be reading Whitstable, his British Fantasy Award-nominated novella.

An unassuming seaside town on the North coast of Kent, Whitstable is known first and foremost for its oysters, but over the centuries it’s also been associated with several celebrities. Volk’s story is an affectionate account of a couple of bleak weeks in the life of an unconventional national treasure: the actor arguably most associated with Hammer Horror in its heyday—Peter Cushing, of course.

It’s 1971, and Peter’s partner Helen has just passed. Lost without the love of his life, he, who made his name playing “cold villains and erudite psychopaths, monster-hunters and those who raised people from the dead,” has come to loathe his lot. “The only person he desperately craved to bring back from the grave he had no power to. It was the one role he couldn’t play. Frankenstein had played God and he had played Frankenstein playing God. Perhaps God had had enough.”

In his grief, Peter finds some small solace in retracing the walks he and his wife once delighted in, one of which takes him to a seat by the beach, where a child recognises him—or rather one of the various characters he played, namely the vampire hunter Van Helsing. In short order, the boy—a misbegotten kid called Carl—politely asks Peter to slay his stepfather, who has so hurt him that Carl, in his innocence, considers him a monster.

Our protagonist is resistant initially:

He felt pathetic and cruel and lost and selfish and small—but he wasn’t responsible for this child. Why should he be ashamed? The vast pain of his own grief was heavy enough to bear without the weight of another’s. Even a child’s. Even a poor, helpless child’s. He was an actor, that was all. Van Helsing was a part, nothing more. All he did was mouth the lines. […] Why was the responsibility his?

But it is, isn’t it? Because the child has come to him for help, and who knows if he’ll ask anyone else? So Peter puts aside his great grief and calls on Carl’s mother. Alas, his visit doesn’t happen as planned. A furious Mrs Drinkwater refuses to accept that her boyfriend is abusing her boy, and then, to make matters worse, when Carl’s stepfather hears about Peter’s interference, he sets about undermining any claims the actor might make:

The scenario had changed radically. The script had been rewritten, drastically. Now at least he knew with some certainty that he daren’t rely on the police or the legal system. His adversary had prepared the ground, cleverly sown the seeds of doubt in a pre-emptive strike against him. If he made an accusation now it was too risky he would be disbelieved and, worse, far worse, the boy would be disbelieved—if the boy even spoke up at all. There was no guarantee he would do so, given his only way of dealing with the situation, it seemed, was through the prism of monsters and monster-hunters.

Published in 2013 to honour what would have been his hundredth birthday, Whitstable is at once a fitting tribute to Peter Cushing and a chilling history of child abuse—two threads so conceptually disconnected that in lesser hands the resulting narrative could have been a travesty, in truth. Thankfully, Volk’s story is as respectful as it is authentic, capturing the place and time of its setting perfectly, including, of course, the prevailing perspectives on such subjects as the exploitation of innocents by people in positions of power.

Carl’s stepfather is more monster than man, but horribly, he’s as human as they come, and Peter isn’t going to solve the poor boy’s problem by slaying his parents—certainly not now that the police are paying attention. Instead, the situation, such as it is—sickening as it is—is resolved, insofar as such things can ever be resolved, by way of more material means.

Bolstered by his belief that his wife is waiting for him, and watching over him in her way—over the course of the conflict, you see, Peter learns to accept his awful loss—the actor summons Carl’s stepfather to the cinema for a climactic conversation cunningly intercut with scenes from The Vampire Lovers, which just so happens to be playing at The Oxford on the day everything comes to a head.

Tense at times, not to mention unsettling, Whitstable is a sensitive story that succeeds as an impeccable portrayal of Peter Cushing and the grief that often grips us after we lose the ones we love, at the same time as presenting a grounded account of honest-to-god human horror. There’s nothing whatsoever speculative about this novella, no, but it’s fitting, I think, to finish with a few words from the aforementioned vampire hunter, who once warned, as Steven Volk notes, that “the Devil’s best trick is that people don’t believe he exists.”

But to be sure, some devils do.

Niall Alexander is an extra-curricular English teacher who reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for The Speculative Scotsman, Strange Horizons, and Tor.com. He’s been known to tweet, twoo.